Spotlight On: Hysteroscopy

This month we are spotlighting Hysteroscopy and articles from the Hysteroscopy Special Interest Group led by Christina Salazar, MD, Co-Chair and Miriam Hanstede, MD, Vice-Chair. SurgeryU features hundreds of high-definition surgical videos from surgeons from around the world. Access to SurgeryU is one of the many benefits included in your AAGL membership. If you would like access to these videos, CME programming, JMIG Journal, and member-only discounts on meetings, join AAGL today. These videos are being made available with public access for a limited time. Click here to join AAGL!

The Mini-Recsectoscope: A Real Innovation or Just Another Trend? By Sergio Haimovich, MD, Alka Kumar, MD, Stina Salazar, MD and Miriam Hanstede, MD

Introduction (Sergio Haimovich) For a hysteroscopist, the mini-resectoscope is the device that best exemplifies the successful advancement of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. The original Gubbini mini-resectoscope was created by Giampietro Gubbini and introduced in 2010 by Tontarra, initially equipped with a 16Fr diameter that later evolved into an oval 14.9Fr device. A few years later, Karl Storz brought to market a 15Fr bipolar mini-resectoscope. Both are versatile tools with different kind of tips including a monopolar/bipolar loop, ball, and needle, and the “cold loop” technique used for enucleation of submucosal fibroids.

The question many ask is how is this new device useful when compared with our “old” conventional resectoscope? First and foremost, there is a significant difference in safety. Due to the smaller 5mm diameter of the mini-resectoscope, there is no need for cervical dilation in most cases. Blind dilation is a step in which false passages and uterine perforations can happen; by negating the need for blind dilation, you benefit by avoiding these common complications. Additionally, the mini-resectoscope can solve almost all intrauterine pathologies except for fibroids greater than 2-3cm in size. This size limitation is based on the dimension of the mini-resectoscope tool and the resulting increase in operative time for myomectomies of larger fibroids.

In addition, using the mini-resectoscope is the natural first step when going from the operating room towards office-based procedures. If you are skilled in resectoscopy your learning curve will be short and only entail getting used to a version of a tool that you are already familiar with. But even if you do not want to start performing intrauterine surgery in an office setting, the small diameter of the mini-resectoscope is a versatile, efficient solution for procedures in the operating room.

The next question should be, what kind of pathologies can the mini-resectoscope help you solve?

Mini-Resectoscope and Polypectomy (Alka Kumar) Endometrial polyps are common, diagnosed in 10% to 40% of women with abnormal uterine bleeding, as well as in 1% to 12% of asymptomatic patients during gynecologic examinations [1]. Moreover, hysteroscopic resection has been adopted as the standard treatment for endometrial polyps because it is easy to perform under general anesthesia and carries a low risk of complications [2].

Mario Franchini et al. concluded office-based polypectomy with the reusable loop electrode resection and 16Fr mini-resectoscope is the most cost-effective approach but requires experienced surgeons. Polypectomy with the mini-resectoscope in an office setting has several advantages, including shorter surgical time, high levels of patient comfort and satisfaction, a large savings for office procedures when compared to inpatient costs, and the 16Fr loop itself being significantly less expensive than the conventional resectoscopic loop [3].

Panos Papalampros et al. published their experience using the mini-resectoscope in the office setting for polyps less than 3 cm. Their focus was to limit surgical time to 15 minutes. They found the 16Fr mini-resectoscope was efficient and polypectomy was feasible without anesthesia [4]. In our own experience, we can confirm that polyps less than 3 cm in size can be efficiently resected with the mini-resectoscope in the office setting.

Mini-Resectoscope and Metroplasty (Alka Kumar) Due to the recent innovations in hysteroscopic equipment and improved surgical techniques, the hysteroscopic management of patients with complex müllerian anomalies using miniaturized instruments is feasible. The mini-resectoscope is an effective treatment option for metroplasty.

Fabiana Divina Fascilla et al. reported performing resection of a uterine septum using an “L-shape” bipolar electrode with a 15Fr office mini-resectoscope by excising 2 triangles of the septum in parallel, obtaining uninterrupted long strips from the fundus to the apex of the septum. These strips were then immediately removed from the uterus and reassembled in vitro to reconstruct a macroscopic, 3-dimensional structure of the septum for complete morphologic and histologic evaluations. By removing the septum as a whole structure, this study redefined the concept of the septum as a complex structure according to the islands of muscle fibers irregularly arranged in vertex in a context of collagen tissue, and similar to the structure of myomas. It appears to deeply involve the anterior and posterior uterine walls, resembling a “reverse letter H” [5].

U Catena et al. reported in a video article a new surgical technique with a step-by-step method combining 3-dimensional ultrasound and hysteroscopic metroplasty, in an office setting, using a 15Fr office mini-resectoscope to treat a dysmorphic T-shaped uterus by resecting the lateral fibromuscular tissue of the uterine walls. No complications occurred and the postoperative hysteroscopy showed a triangular and symmetrical uterine cavity without any adhesions [6]. Similarly, Attilio Di Spiezio Sardo demonstrated hysteroscopic management of this complex müllerian anomaly using miniaturized hysteroscopic instruments, including the mini-resectoscope. No complications were encountered [7].

Mini-Resectoscope and Isthmocele (Alka Kumar) The cesarean scar defect (CSD), also defined as a niche or isthmocele, is often diagnosed during a transvaginal sonography or sonohysterography (SIS) with either gel or saline infusion. It usually appears as a wedge-shaped anechoic area inside of the myometrium at the site of the previous cesarean section and can best be identified during the early follicular phase because of its detection by the accumulated menstrual blood [8]. CSD are often associated with postmenstrual abnormal uterine bleeding with a dark red or brown discharge, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, and/or secondary infertility [9−11]. Since its first description [12], multiple techniques have been used for CSD treatment: reconstructive surgery, including laparoscopic or robot-assisted excision; vaginal repair; and channel-like resectoscopic treatment [13−17]. To date, several studies have been published on this last technique using the 26Fr resectoscope by resecting the inferior/proximal and superior/distal edges to correct the defect [18−22].

Isthmoplasty with a 16Fr mini-resectoscope is as effective as isthmoplasty with a 26Fr resectoscope in reducing abnormal uterine bleeding and suprapubic pelvic pain. It is associated with a significant reduction in overall surgical time given cervical dilatation is not necessary and one can employ the vaginoscopic approach for entry. There is also reduced incidence of cervical lacerations, which, in 55% of uterine perforations, are directly related to entry [23]. Moreover, isthmoplasty with a 16Fr mini-resectoscope is associated with a reduced amount of distension medium instilled and of fluid absorbed during the procedure; smaller diameter instruments are less likely to cause fluid overload owing to smaller diameter inflow channels [24]. No intravasation syndrome has been reported with use of the mini-resectoscope. 16Fr mini-resectoscope reduces the postoperative pain perception and increases patient satisfaction. Use of a 16Fr mini-resectoscope has been reported to be safe and effective for isthmoplasty and should be considered, in our opinion, a new alternative to the traditional resectoscope

Mini-Resectoscope and Myoma (Stina Salazar) Leiomyoma are the most common pelvic neoplasm in females [25]. Myomas that are submucous in location (FIGO type 0, 1, and 2) are associated with increased risk of miscarriage as well as heavy menstrual flow. Based on their FIGO location, they are amenable to resection as therapeutic treatment. While the mini-resectoscope can certainly be used successfully for myomectomy in the traditional operating room suite, office-based hysteroscopic approaches allow the surgeon to utilize the “see and treat” strategy for workup of structural causes for abnormal uterine bleeding, avoiding the need for general anesthesia [26, 27, 28]. In a systematic review and meta-analysis, administration of paracervical anesthesia was associated with a significant reduction in pain with operative hysteroscopic procedures [26]. García-Jiménez et al. published a cohort series of 59 patients that underwent hysteroscopic myomectomy performed in office with the mini-resectoscope and reported that 75% had a complete resection with a mean resection time of 13.5 minutes, high levels of patient satisfaction and low overall pain associated with the procedure with paracervical block [28]. Valero et al. similarly concluded that in a cohort of patients that underwent office-based hysteroscopic myomectomy with the mini-resectoscope, 81% were able to achieve complete resection with a mean resection time of 13.4 minutes, with low pain scores with a paracervical block alone for pain control, high patient satisfaction, and with very low complication rates of 0.1% for uterine perforation [29].

To aid in cervical preparation, misoprostol can be administered prior to the procedure either 600mcg vaginally the night before or 400mcg buccally 2-3 hours before. Extraction of the fibroid specimen chips and fragments frequently poses a challenge for the surgeon. The AAGL Hysteroscopy SIG recommends an expert tip for surgeons that can save time and decrease patient discomfort: grasp the fibroid specimens in the loop and leave the outer sheath in place while removing the entire hysteroscope – this allows the surgeon to go in and out of the cavity easily to remove specimen without directly needing to reinsert through the cervix. Avoiding multiple entries into the uterine cavity also decreases the overall risk of complications.

Discussion and Conclusions (Miriam Hanstede) Ever since its first report by Neuwirth in 1978, the resectoscope has remained a most efficient instrument for hysteroscopic surgery. The technical progress in recent years with the introduction of miniaturization of resectoscope, represent a new alternative in the treatment of uterine lesions. The introduction of smaller-diameter instruments is a step forward in intrauterine surgery in terms of efficacy, safety, costs and clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction. The AAGL Hysteroscopy SIG feels the mini-resectoscope represents true innovation and that the evidence demonstrates its efficacy in treating polyps, Mullerian anomalies, isthmoceles and myomas. Furthermore, the mini-resectoscope reflects the advancements in minimally invasive surgery and value-based care that shift from inpatient hysteroscopic procedures to an office or outpatient setting and allows patients to be diagnosed and treated on a ‘‘see and treat’’ basis.

References

- Salim S, Won H, Nesbitt-Hawes E, Campbell N, Abbott J. Diagnosis and management of endometrial polyps: a critical review of the literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:569–581.

- Lieng M, Istre O, Qvigstad E. Treatment of endometrial polyps: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89:992–1002.

- Franchini F, Lippi G, Calzolari S, Giarrè G,Gubbini G, Catena U, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Florio P. Hysteroscopic Endometrial Polypectomy: Clinical and Economic Data in Decision Making. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011; 418-425

- Panos Papalampros, Pietro Gambadauro, Nikolaos Papadopoulos, Dimitris Polyzos, Lynne Chapman, Adam Magos. The mini-resectoscope: A new instrument for office hysteroscopic surgery Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica. 2009; 88: 227230

- Fabiana Divina Fascilla, Leonardo Resta, Rossella Cannone, Domenico De Palma, Oronzo Ruggiero Ceci, Vera Loizzi, Attilio Di Spiezio Sardo, Rudi Campo, Ettore Cicinelli, Stefano Bettocchi. Resectoscopic Metroplasty with Uterine Septum Excision: A Histologic Analysis of the Uterine Septum

- J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2020; 27(6):1287-1294 U Catena, R Campo, G Bolomini, M C Moruzzi, V Verdecchia, F Nardelli, I Romito, F Camolo, V La Manna, M M Ianieri, G Scambia, A C Testa. New approach for T-shaped uterus: Metroplasty with resection of lateral fibromuscular tissue using a 15 Fr miniresectoscope. A step-by-step technique. Facts Views Vis Obgyn 2021; 13(1):67-71.

- Attilio Di Spiezio Sardo, Alfonzo Manzi, Brunella Zizolfi, Pierluigi Giampaolino, Jose Carugno, Grigoris Grimbizis. The step-by-step hysteroscopic treatment of patients with vaginal and complete uterine septum with double cervix Fertil Steril 2021; 116(2):602-604.

- Tulandi T, Cohen A. Emerging manifestations of cesarean scar defect in reproductive-aged women. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:893–902.

- Tower AM, Frishman GN. Cesarean scar defects: an under recognizedcause of abnormal uterine bleeding and other gynecologic complications.J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20:562–572.

- Bij de Vaate AJ, van der Voet LF, Naji O, et al.. Prevalence, potential risk factors for development and symptoms related to the presence of uterine niches following cesarean section: systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;43:372–382.

- Menada Valenzano M, Lijoi D, Mistrangelo E, Costantini S, Ragni N. Vaginal ultrasonographic and hysterosonographic evaluation of the low transverse incision after caesarean section: correlation with gynaecological symptoms. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;61:216–222.

- Morris H. Surgical pathology of the lower uterine segment caesarean section scar: is the scar a source of clinical symptoms? Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1995;14:16–20.

- Api M, Boza A, Gorgen H, Api O. Should cesarean scar defect be treated laparoscopically? A case report and review of the literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:1145–1152.

- Yalcinkaya TM, Akar ME, Kammire LD, Johnston-MacAnanny EB, Mertz HL. Robotic- assisted laparoscopic repair of symptomatic cesarean scar defect: a report of two cases. J Reprod Med. 2011;56:265–270.

- Chen H, Wang H, Zhou J, Xiong Y, Wang X. Vaginal repair of cesarean section scar diverticula diagnosed in non-pregnant women. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:526–534.

- Florio P, Filippeschi M, Moncini I, Marra E, Franchini M, Gubbini G. Hysteroscopic treatment of the cesarean-induced isthmocele in restoring infertility. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;24:180–186.

- Casadio P, Gubbini G, Morra C, Franchini M, Paradisi R, Seracchioli R. Channel-like 360° Isthmocele treatment with a 16F miniresectoscope: a step-by-step technique. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:1229–1230.

- Fabres C, Arriagada P, Fern andez C, Mackenna A, Zegers F, Fernandez Surgical treatment and follow-up of women with intermenstrual bleeding due to cesarean section scar defect. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12:25–28.

- Gubbini G, Casadio P, Marra E. Resectoscopic correction of the “isthmocele” in women with postmenstrual abnormal uterine bleeding and secondary infertility. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:172–175.

- Shapira M, Mashiach R, Meller N, et al.. Clinical success rate of extensive hysteroscopic caesarean scar defect (CSD) excision and correlation to histological findings. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:129–

- Sanders AP, Murji A. Hysteroscopic repair of cesarean scar isthmocele. Fertil Steril. 2018;110:555–556.

- Raimondo G, Grifone G, Raimondo D, Seracchioli R, Scambia G, Masciullo V. Hysteroscopic treatment of symptomatic cesareaninduced isthmocele: a prospective study. J Minim Invas Gynecol. 2015;22:297–301.

- The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Green-top guideline no. 59: best practice in outpatient hysteroscopy. Availablen at: https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/ gtg59hysteroscopy.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2011.

- Umranikar S, Clark TJ, Saridogan E, et al.. BSGE/ESGE guideline on management of fluid distension media in operative hysteroscopy.Gynecol Surg. 2016;13:289–303.

- Day Baird, Donna et al.. “High Cumulative Incidence of Uterine Leiomyoma in Black and White Women: Ultrasound Evidence.” American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 188.1 (2003): 100–107

- Munro, Malcolm G., and Philip G. Brooks. “Use of Local Anesthesia for Office Diagnostic and Operative Hysteroscopy.” Journal of minimally invasive gynecology 17.6 (2010): 709–718.

- Papalampros, Panos et al.. “The Mini-Resectoscope: A New Instrument for Office Hysteroscopic Surgery.” Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica 88.2 (2009): 227–230.

- Fernandez, Hervé. “Update on the Management of Menometrorrhagia: New Surgical Approaches.” Gynecological endocrinology 27.S1 (2011): 1131–1136.

- García-Jiménez, Rocío et al.. “Evaluación de la efectividad y satisfacción de las pacientes tras miomectomía histeroscópica en consulta.” Revista chilena de obstetricia y ginecología 2021;86.4.

Authors: Sergio Haimovich, MD, Alka Kumar, MD, Stina Salazar, MD and Miriam Hanstede, MMF are members of the AAGL Hysteroscopy Special Interest Group. Prof. Sergio Haimovich, MD is Head of the Hysteroscopy Unit at the Del Mar University Hospital in Barcelona, Spain. Alka Kumar, MD is Director of Women’s Health Centre in Jaipur, India. Christina “Stina” Salazar, MD is Assistant Professor of Women’s Health, UT Health Austin Dell Medical School in Austin, TX. Miriam Hanstede, MMF is a physician at Spaarne Gasthuis Hospital, Netherlands.

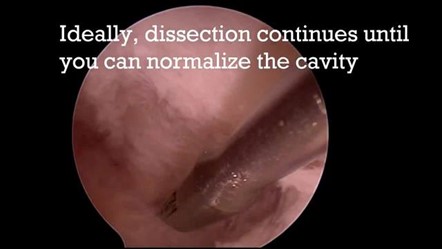

Spotlight Video One: Resection of Intra-uterine Pathology with 15 French Resectoscope (5mm) in the Office with No Anesthesia by Valencia Miller, MD, Stephanie Morris, MD and Keith Isaacson, MD.

The Hysteroscopy SIG selected this video for its demonstration of the advantages of the mini-resectoscope use in the office for various pathologies. The video highlights best candidates for this approach and reviews the office setup needed.

Spotlight Video Two: Video Cookbook: Office Lysis of Adhesions for Patients with Asherman’s by Christina A. Salazar, MD and Keith Isaacson, MD.

The Hysteroscopy SIG selected this video for its simplified approach that breaks down the critical steps to clinical presentation and surgical management of patients with Asherman’s Syndrome. Considerations for postoperative management are also reviewed.

Most Difficult Case by Jude Okohue, MD

Mrs. AA, a 36-year-old para G2P0020 married for 6 years to a 44-year-old man. She had been unable to conceive despite regular, unprotected sexual intercourse. She had two previous pregnancy terminations before marriage at eight weeks and 16 weeks gestational ages, respectively, by dilatation and evacuation. Following her last pregnancy termination, she developed a copious non-offensive vaginal discharge, for which she was prescribed a combination of antibiotics. Her menstrual cycle remained regular with no dysmenorrhoea or menorrhagia.

Before coming to us, she had presented at another gynecology clinic for evaluation of secondary subfertility. A transvaginal ultrasound scan (TVS) revealed echogenic areas with dense shadowing within the endometrial cavity. Suspicious of retained fetal bones, an indication to rule out intrauterine synechiae was made by the sonologist. Mrs. AA subsequently underwent several attempts at blind dilatation and curettage to remove the bones, and later developed amenorrhea. She was referred to a second gynecology center, where a repeat TVS revealed the same findings. Her hormone profile results were within the normal range. Hysteroscopy was performed, and findings included cervical adhesions and vertical and horizontal ridges within the endometrial cavity. The adhesions were separated with 5F hysteroscopy scissors while the suspected fetal bones were removed with 5F grasper. An intrauterine barrier gel or stent was not placed after the procedure. It was also not clear if she was placed on any post-operative hormonal treatments. Histology confirmed fetal bones. Mrs. AA menstruated for two cycles following the procedure before the amenorrhea reoccurred.

She was subsequently referred to our center for further management. At presentation, a repeat hysteroscopy was performed. Due to cervical adhesions, there was difficulty negotiating the cervical canal and we could not find the entry point into the endometrial cavity. We explored a tiny hole through which secretions were being sucked in and subsequently encountered pinkish tissue, which indicated possible endocervical canal epithelium. This was explored carefully to identify an entry into the endometrial cavity and was observed to be deviated towards the patient’s left. (See Video 1)

Adhesiolysis was performed with a single, 5 mm, compact inflow and outflow channel (Richard Wolf, Knittlingen, Germany), including a 2.9 mm, 25-degree telescope, and 5Fr rigid hysteroscopy scissors. Normal saline was used as the distension medium. A normal fundus was subsequently encountered, and bilateral tubal ostia were visualized. The adhesions were graded as moderate (score of 8) using the American Fertility Society classification system. Attempts at inserting a Foley catheter balloon were unsuccessful. An intrauterine device (IUD) was also introduced, but a post-operative transvaginal scan revealed incorrect positioning within the endometrial cavity. The IUD was therefore eventually removed.

Mrs. AA was subsequently placed on sequential combined hormonal therapy for cyclical withdrawal bleed. These comprised estradiol valerate (Progynova®, Bayer Plc, Reading, United Kingdom) 2mg twice a day for 21 days. And the progestogen, Norethisterone tablets (Primolut N®, Bayer Plc, Reading, United Kingdom) 5mg thrice a day for seven days, to commence on day 15 of estradiol valerate. Her menses returned with good flow and lasting four days with no associated dysmenorrhea. However, three months after the hysteroscopic adhesiolysis, she again developed amenorrhea. A third hysteroscopy was carried out (the second in our center) with the same findings as in previous procedure (See Video 2).

Following successful adhesiolysis, neither Foley catheter nor IUD could be introduced into the uterine cavity due to the angulation of the cervical canal. Attempts to introduce the catheter balloon under direct hysteroscopic and ultrasound scan visualization were also unsuccessful. Therefore, a decision was taken to instill an intrauterine gel instead. The instillation was under direct vision. Estradiol and progesterone tablets were again prescribed for one cycle. Mrs. AA menstruated after that and achieved spontaneous conception after three months while being worked up for possible assisted conception. She had an elective cesarean section at term, the indication being an older nullipara with placenta previa. The result was a 3.1kg female neonate with good APGAR scores.

Discussion

Asherman syndrome is an acquired condition that describes intrauterine adhesions (IUA) that commonly occur in association with symptoms such as menstrual irregularities, recurrent pregnancy loss, and infertility. Heinrich Fritsch first described the condition in 1894, and it was later characterized by Joseph Asherman in 1948 (1). Asherman syndrome is most often preceded by pregnancy-related procedures such as the curettage of a peripartum uterus. However, intrauterine adhesions can also be identified following a caesarean section, abdominal or hysteroscopic/laparoscopic myomectomy, use of B-Lynch compression sutures, chronic infections such as schistosomiasis and tuberculosis of the genital tract, as well as surgeries for Mullerian duct abnormalities (2,3). Mrs. AA developed IUA following repeated dilatation and curettage to remove retained fetal bones. Unfortunately, the fetal bones were retained following termination of pregnancy by dilatation and evacuation, confirming the dangers inherent with second-trimester dilatation and evacuation (4).

The diagnosis of IUA in the index case was made via hysteroscopy. Hysteroscopy is considered the gold standard in the diagnosis and treatment of IUA (5,6). It enables the direct evaluation and categorization of the adhesions, including estimating the proportion of healthy endometrial tissue. Other modalities for evaluation of IUA include hysterosalpingography, 2D/3D ultrasonography, and saline infusion sonography.

Historically, Asherman syndrome was managed by blind adhesiolysis. This did not allow for proper visualization of the IUA. Hysteroscopy ensures that the adhesions are lysed directly. The IUAs are usually separated with cold scissors. A recent study comparing cold scissors versus electrocautery found cold scissors to be more efficient in preventing IUA recurrence, increasing menstrual flow, and shortening operating time (7). Mrs. AA had hysteroscopic adhesiolysis using 5F hysteroscopy scissors. There was difficulty determining the route through which to access the endometrial cavity. Under this circumstance, we relied upon the finding of the pinkish columnar epithelium against the whitish appearing muscle fibers, which subsequently led into the endometrial cavity. While both tubal ostia were visualized, the abridged video only shows one ostium. Sometimes, hidden pockets of endometrial cavities present as dark areas, resulting from the absorption of light (8). Exploring these dark areas might also lead to the endometrial cavity. To further guide against complications such as uterine perforations in cases of severe IUA, concomitant use of ultrasonography, fluoroscopy, and laparoscopy are commonly used. While a transabdominal ultrasound scan aims to guide the hysteroscope towards the uterine cavity, fluoroscopy helps identify hidden pockets of endometrial tissue behind or above adhesions. Laparoscopy helps detect a perforation when it occurs and prevents injury to the bowel. There is, however, no evidence that one method is superior to the other. None were used in the management of this case.

One of the challenges in the management of IUA is the risk of adhesion reformation following treatment. Hanstede and colleagues (9) reported a 28.7% recurrence rate following 1 – 3 attempts at hysteroscopic adhesiolysis. Strategies aimed at preventing adhesion reformation include the use of barrier agents such as the intrauterine device, intrauterine pediatric Foley catheter, intrauterine balloon stent, and the intrauterine gel. The aim is to separate the walls of the uterine cavity, allowing for healing. Unfortunately, attempts at inserting the IUD or Foley catheter balloon were unsuccessful in this case due to the sharp angulation of the cervical canal and uterus. Intrauterine gel was instilled into the uterine cavity following hysteroscopic adhesiolysis at the second failed attempt because neither stent nor IUD were insertable. This finally led to the sustenance of her menstrual cycle and subsequent pregnancy three months later. While a randomized controlled study found the intrauterine balloon and IUD to be more effective than the gel in preventing adhesion recurrence, another study showed a 14% recurrence rate with the application of the gel, compared to 32% with no treatment (10,11). Despite the above, there is still no solid evidence that any of these methods prevent adhesion reformation (12). In this case, the non-recurrence of IUA and amenorrhoea occurred after placement of a gel barrier to separate the uterine walls. Other methods used in preventing IUA include using a fetal amnion graft wrapped around a Foley catheter balloon (13). The place of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in preventing adhesion reformation is still not fully established. While some studies showed some benefits, others concluded otherwise (14). Reports suggest that stem cell therapy might give some promising results (15).

Conclusion

Mrs. AA eventually had an elective caesarean section at term on account of placenta previa. Abnormal placentation is a known complication of Asherman syndrome, regardless of whether the lysis of adhesions is successful (16). The management of Asherman syndrome remains a dilemma. Hysteroscopy is still the gold standard in the diagnosis and management of the disease. Nevertheless, as this case shows, difficult cases may require several attempts. Furthermore, in the absence of uterine stenting, an anti-adhesion barrier combined with sequential hormonal support appeared to enhance chances of successful hysteroscopic adhesiolysis.

References

- Asherman JG. Amenorrhoea traumatica (atretica). J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1948;55:23–30

- March CM. Asherman’s syndrome. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29:83–94.

- Rasheed SM, Amin MM, Abd Ellah AH, Abo Elhassan AM, El Zahry MA, Wahab HA. Reproductive performance after conservative surgical treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;124:248–52.

- Okohue JE. The incidence of retained fetal bones after 1,002 hysteroscopies in an environment with restrictive abortion laws. Trop J Obs Gyne 2019; 36(2): 249 – 41.

- Santamaria X, Liu JH, Lusine A, et al. Should we consider alternative therapies to operative hysteroscopy for the treatment of Asherman syndrome? Fertil Steril. 2020; 113(2): 511 – 21.

- Okohue JE, Okohue JO. Establishing a Low-Budget Hysteroscopy Unit in a Resource-Poor Setting. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2020;9(1):18-23.

- Yang L, Wang L, Chen Y, et al. Cold scissors versus electrosurgery for hysteroscopic adhesiolysis: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(17):e25676.

- Emanuel MH, Hanstede M. Hysteroscopic treatment of Asherman syndrome. In: Hysteroscopy. Tinelli A, Pacheco LA, Haimovich S (eds). Springer International Publishing, Cham Switzerland. 2018; 709 – 18.

- Hanstede MM, van der Meij E, Goedemans L, et al. Results of centralized Asherman surgery, 2003-2013. Fertil Steril. 2015 Dec;104(6):1561-8.

- Lin XN, Zhou F, Wei ML, et al. Randomized, controlled trial comparing the efficacy of intrauterine balloon and intrauterine contraceptive device in the prevention of adhesion reformation after hysteroscopic adhesiolysis. Fertil Steril. 2015 Jul;104(1):235-40.

- Acunzo G, Guida M, Pellicano M, et al. Effectiveness of auto-cross-linked hyaluronic acid gel in the prevention of intrauterine adhesions after hysteroscopic adhesiolysis: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(9):1918-21.

- Bosteels J, Weyers S, D’ Hooghe TM, et al. Anti-adhesion therapy for treatment of female subfertility. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2017; 11(11): CD011110.

- Peng X, Li T, Zhao Y et al. Safety and efficacy of amnion graft in preventing reformation of intrauterine adhesions. JMIG 2017; 24(7): 1204-10

- Javaheri A, Kianfar K, Pourmasumi S, et al. Platelet-rich plasma in the management of Asherman’s syndrome: An RCT [published correction appears in Int J Reprod Biomed. 2021 Apr 22;19(4):392]. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2020;18(2):113-120.

- Benor A, Gay S, DeCherney A. An update on stem cell therapy for Asherman syndrome. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020 Jul;37(7):1511-1529.

16. Zhang L, Wang M, Shang X, et al. The incidence of placenta related disease after the hysteroscopic adhesiolysis in patients with intrauterine adhesions. Taiwanese J of Obstet and Gynecol, 2020; 59(4): 575-9.

Author: Dr. Okohue is a board member on the AAGL Hysteroscopy SIG, surgeon at Gynescope Specialist Hospital and Professor at Madonna University in Nigeria.

The post Spotlight On: Hysteroscopy appeared first on NewsScope.